Suicide.

Just say the word, and conversation halts. It’s perhaps the last taboo. It’s also sudden. Tragic. Violent. But preventable?

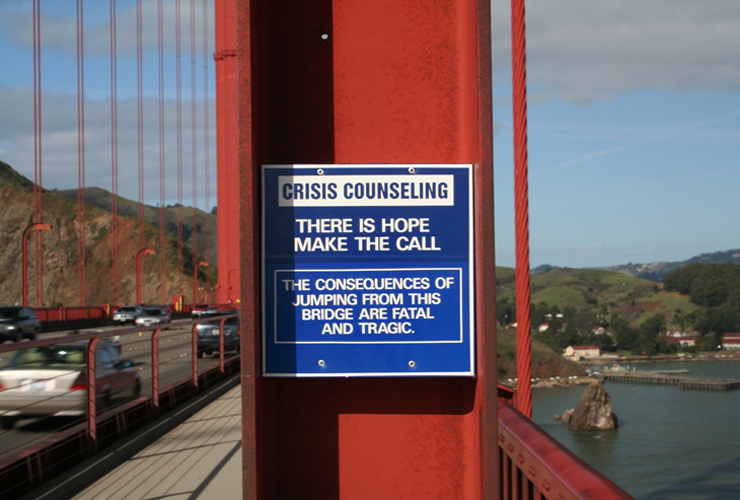

As a suicide prevention initiative, this sign on California’s Golden Gate Bridge promotes a special telephone that connects to a crisis hotline.

And that in claiming 31,655 lives in 2002, suicide is a leading threat to public health and well-being in our country.

But how can someone be thwarted from taking their life if they are determined to do so? Isn’t suicide a personal choice, a reflection of perhaps the supreme personal right – the right to determine when to die?

Not the case, according to former Surgeon General David Satcher, MD, PhD. And he has plenty of support.

“Even in the public health model, you have to recognize that suicide is the very sad aftermath of a psychiatric disorder – according to 90 percent of psychological autopsies,” says Madelyn Gould, professor of psychiatry and public health at Columbia University. exacts on individuals and society.

That toll is relentless and far-reaching, including loss and suffering from both completed suicides plus suicidal behaviors and attempts.

“For every suicide death there are scores of family and friends whose lives are devastated emotionally, socially and economically,” notes Catherine Le Galés-Camus with the World Health Organization, adding that more people die by suicide than from all homicides and wars combined. “Suicide is a tragic global health problem.”

But acknowledging suicide as a threat to public health is only the first step toward curbing its effects.

Also vital are a knowledge base, the public and political will to support change and generate resources and a social strategy to accomplish this change.

These elements are cornerstones of the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention (NSSP). Released in 2001 by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the NSSP summons partners across many sectors of society – public and private, for profit and nonprofit.

The goal? To build and sustain a true national effort to prevent suicide – one that is grounded at the local level.

Not my problem

Attempted suicide, completed suicide and their aftermath are not just personal problems or family problems or community problems. They are societal problems.

How? Because someone’s suicide attempt or completion leaves us all a bit shaken, somewhat vulnerable.

But viewing suicide as everybody’s problem is not widely accepted or even talked about.

“Suicide is a very difficult topic … people are at a loss for what to say and do,” says Ileana Arias, PhD, acting director of the National Center for Injury Prevention and Conrol at the CDC. “It’s not a polite thing. It makes people very uncomfortable.”

Researcher Eric Caine agrees. Caine is co-director of the Center for the Study and Prevention of Suicide at the University of Rochester Medical Center.

“There’s a stigma, a feeling that ‘it’s not my problem. It’s very unfortunate that suicide happened to a friend’s uncle, but how does that affect me?’ ” says Caine of the sense of separateness many of us feel when considering the death of someone by suicide.

Not only is that separateness untrue, it feeds a stigma and blocks suicide from being adequately dealt with.

“There’s a sense of fatalism about ‘life is what it is,’ ” continues Caine.

Yet when it comes to suicide and its prevention, nothing could be further from the truth.

A bigger issue

Perhaps fundamental to preventing suicide is not the issue of suicide itself, but all the contributors that can lead to suicide.

It’s about helping a person before they reach the edge of the cliff when they’re miserable, have lost so much and think that life is not worth living.

“It’s about getting to the high school student who’s having problems before they drop out,” Caine suggests. “It’s about getting to the parent before substance abuse erodes their quality of life or before they resort to domestic violence. It’s about getting to the elderly person with untreated pain, loss of function and social isolation before they consider suicide.”

If life’s problems and pressures could form a pyramid, suicide would be at the top of that pyramid. It’s an analogy used often when considering how suicide can be prevented.

“The public health approach (to suicide prevention) says, ‘Let’s get to the base of the pyramid,’ ” notes Caine. “We’re not here just to deal with suicide. The question really is – as a society are we ready to deal with the challenges associated with school dropouts, alcoholism, domestic violence? Many people recognize these as problems, but they don’t hook them up together. Suicide prevention opens the door to understanding all of these common risk factors.”

Focusing on everybody

Paying attention to not only people at high risk but to those at lesser risk – and intervening before these individuals move to high-risk status. It’s a cornerstone of preventive medicine – and of a public health approach to suicide prevention.

But does it work?

Can lowering rates of school absenteeism, alcoholism, domestic violence and other issues also lower rates of suicide? Yes, say researchers who have studied a landmark community-based suicide prevention program, one that showed a striking 33 percent reduction in risk for suicide over a 6-year period.

Developed and implemented by the United States Air Force, this program is the first ever to suggest that suicide is a preventable public health problem. And not only did suicides decline, but severe family violence decreased 54 percent, homicides dropped 51 percent and accidental deaths declined 18 percent.

“This is maybe the thing that astounded me the most – the decline in family violence, in accidents, homicides. The spillover effect,” says Charles H. “Chip” Roadman II, MD, CNA, former surgeon general of the Air Force and one of the architects of the groundbreaking USAF suicide prevention program. “We began to change the culture. And it was not what we set out to do.”

Preventing suicide is about helping a person before they reach the edge of the cliff when they’re miserable, have lost so much and think that life is not worth living. closed community like the Air Force and certainly not in much more diverse civilian communities.

Yet the concept of suicide as a community concern, a public health problem and not an isolated personal choice, is fundamental to its prevention.

Barriers are formidable

How prepared are communities throughout the United States to address suicide as a preventable public health problem?

Not very, according to a recent assessment by a pivotal U.S. presidential commission. “… the mental health delivery system is fragmented and in disarray … lead[ing] to unnecessary and costly disability, homelessness, school failure and incarceration,” according to the November 2002 Interim Report from the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health.

The commission’s final report notes that “in many communities, access to quality care is poor, resulting in wasted resources and lost opportunities for recovery. More individuals could recover from even the most serious mental illnesses if they had access in their communities to treatment and supports that are tailored to their needs.”

What are some of the barriers to effective community delivery of mental health services?

Stigma that surrounds mental illnesses. Treatment limitations and financial requirements placed on mental health benefits in private health insurance. And a sorely fragmented mental health service delivery system.

Given these and other obstacles, communities face daunting challenges in developing suicide prevention programs, and then implementing, evaluating and creating positive outcomes for these. And yet communities are uniquely suited to meet local needs more effectively than a centralized “one-size-fits-all” dogma implemented at the state or national level.

As with the Air Force program, when it comes to suicide prevention, leadership is key – at the community, county, state and national levels. Unless top leadership fully endorses, advocates, authorizes and mandates that suicide prevention will be a priority, prevention efforts will have limited success.

A system-wide transformation

A. Kathryn Power has a big job. As director of the Center for Mental Health Services, a component of SAMHSA, an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Power, MEd leads the charge at the federal level in transforming mental health care in America called for by the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health – and, in doing so, advancing the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention.

“We see suicide prevention as an element of this transformation,” notes Power. “We believe that suicide is a very serious public health challenge, one that hasn’t received the attention it deserves.”

That level of attention is changing, in part with the inclusion of $11.5 million for suicide prevention in the fiscal year 2006 federal budget. Much of that is in response to 2004 Congressional passage of the Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Act calling for suicide prevention funding for youth and college student populations. And advocates are taking notice.

“For the first time ever there are budget numbers going to the Hill for suicide prevention,” says Jerry Reed, MSW, Executive Director of SPAN USA, a national grassroots advocacy organization. “Funding at SAMHSA went from $6 million to $16.5 million in one year. That’s great news. Is it adequate given the impact of suicide in our country? In a word, no. But it’s a start.”