Robert Becker was a Wisconsin farm boy who was educated only through middle school before he dropped out to keep the family farm afloat.

Robert Becker was a Wisconsin farm boy who was educated only through middle school before he dropped out to keep the family farm afloat.

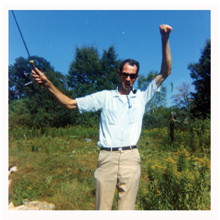

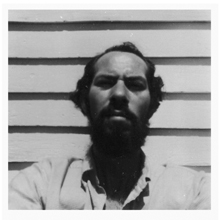

A lanky kid, Robert was 6’ 9’’ by his 18th birthday. Before he turned 44 years of age, he was dead by suicide. Robert’s only daughter was 8 years old at the time of his death.

Her dad’s suicide has taken its toll on Sherry Becker of Cedarburg, Wisconsin.

Sherry Becker lost her dad Robert to suicide in 1977.

“Every single day it haunted me,” says Sherry of her father’s suicide in 1977. She engaged in cutting and suicidal ideation as a teenager, and struggled for years with unhealthy relationships with men who are suicidal or alcoholic—just as her dad was. “I think I was trying to help them live because I couldn’t help my dad live,” adds Sherry.

Sherry’s story is not uncommon. It illustrates societal effects of suicide among men in the so-called middle years of life—ages 25-54. The greatest burdens of suicide, in terms of potential years of life lost or potential earnings lost, occur in this age group. Yet theirs is a group too often overlooked by prevention efforts.

“Suicide research related to men in their middle years is virtually nonexistent,” notes Gregory K. Brown, PhD, with the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania. “This is surprising given the public health significance of the problem. Increased community efforts that voice concern about this problem are sorely needed.” Brown suggests one approach for preventing suicide in this population is to identify individuals with major risk factors for suicide.

“Men who attempt suicide are frequently identified in medical care settings including emergency departments, behavioral health care settings or addiction treatment settings,” notes Brown. “They frequently suffer from severe mental illness including major depression, bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder in war veterans.”

Substance-use disorders are also common among this population, according to Brown, as are major social problems such as lack of housing and unemployment.

“Individuals with multiple psychiatric, addiction and major social needs are problematic because there is very little coordination of care among behavioral health care, chemical dependency and social service programs,” Brown notes. The end result of this lack of coordinated care? “Patients most likely to kill themselves (as evidenced by their suicidal behavior) are the most likely to fall through the cracks in terms of receiving desperately needed treatment and services,” he adds.

Brown, along with Aaron T. Beck, MD, and colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania have recently developed and tested an intervention for both men and women who attempt suicide. It includes targeted cognitive therapy and case management services to treat this difficult population.

“We’ve found that by using this approach, we can reduce the rate of repeat suicide attempts by 50 percent among those who attempt suicide,” adds Brown.

For more on using cognitive therapy to reduce suicide risk, read Cognitive Therapy for Suicidal Patients: Scientific and Clinical Applications, By Amy Wenzel, PhD; Gregory K. Brown, PhD; and Aaron T. Beck, MD, November, 2008, American Psychological Association.