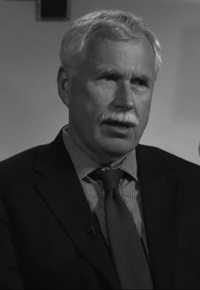

“The current mental health delivery system is inadequate and unprepared to address the needs associated with the anticipated growth in the number of older persons requiring treatment for late-life mental disorders,” says Michael Hogan, PhD, former chair of the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health.

“The current mental health delivery system is inadequate and unprepared to address the needs associated with the anticipated growth in the number of older persons requiring treatment for late-life mental disorders,” says Michael Hogan, PhD, former chair of the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health.

Hogan cites three policy areas that must be addressed to ensure adequate and appropriate mental health care and suicide prevention for older adults:

1. Improved access to services

Older persons are most likely to tap mental health care in home- and community-based settings. Yet services covered by insurance are typically in a physician’s office setting. “We need a redesign of the mental health system to respond to the preferences and needs of older persons and the mismatch between covered and preferred services,” notes Hogan. This includes better coordination across the federal aging network, mental health, general health and long-term care sectors. The focus? It should be on care management and care plan oversight for community-based, culturally sensitive and age-appropriate services for older persons, according to Hogan and the New Freedom Commission. This should include coordination of providers and systems for delivering mental health, medical, social and long-term care services. It should also include revamped

Medicare reimbursement policies that are in sync with recent advances in care and provide timely access to mental health care.

2. Better, more integrated services

Older patients undergoing treatment for mental disorders do best in a collaborative setting, according to recent research. This setting is a primary care one, with a mental health provider to provide assessment, clinical treatment services and coordination with the PCP. Evidence-based models such as IMPACT and PROSPECT are based on this collaborative approach with a cross-functional team highly engaged with each patient; these models have shown noteworthy success in treatment of mental illnesses in aging populations.

3. More health care workers

The rise in coming numbers of older Americans shines a stark light on a chilling reality: Given current estimates, there will not be enough health care workers, caregivers and peer support staff to meet the mental health needs of this population. “There is a pressing need to develop a workforce with specialized training in gerontology and geriatric mental health,” notes Hogan. “We need HHS, state mental health authorities and other entities to develop a workforce with specialized skills to provide services to older persons with mental disorders. This includes psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, social workers and frontline service providers. It also includes enhancing family caregiver and peer support services.”