“A child can’t be depressed.”

It’s what we adults told ourselves for years, when mood disorders and thoughts of suicide were shrouded in stigma and shame.

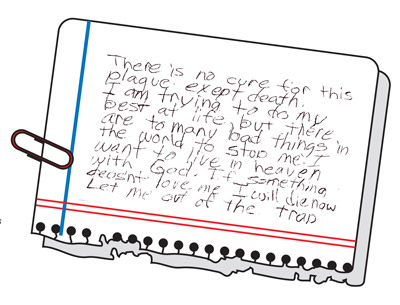

Today we know better. We’ve heard about depression. We’ve heard about substance abuse. We’ve heard about bipolar disorder and the risk factors for suicide. Yet it’s still so difficult to conceive the inner torment that could spur a child to consider ending his or her life.

It was back in the 1990s that I first became involved in working with suicidal youths when I worked in the emergency room of a hospital in the Bronx. There was very little in the scientific literature then about suicidal children. Yet I saw so many youngsters who were so ill.

Children as young as 5 who were severely psychotic with bizarre preoccupations and thoughts of suicide. A morbidly depressed 8-year-old child with a very strong genetic history of mood disorders. A 12-year-old youngster who completed suicide after enduring years of bullying. Children who experienced the worst kind of loss, including the suicide of a parent.

The intensity of their response was exceptional and heartbreaking. Preventing someone—including a child—from taking their life requires we do some key things.

First, we need to identify those who are more likely to attempt or complete suicide. Once we’ve identified these people at risk, wemay be able to intervene before they get too close to the edge.

Second, we need to know what to do to help a suicidal child back away from that abyss.

Perhaps most important, we need to recognize that children do indeed kill themselves, and many more attempt suicide.

Our nation’s mortality data do not lie. Rates of suicide in children age 10–14 have increased since the 1950s by 300 percent. And suicide is today the third leading killer of young people ages 10–24. Only when we accept this difficult truth can we reduce suicide among those most vulnerable among us—our children.